The Pentagon UFOs - 2004, 2014, 2015

The Pentagon UFO videos are selected visual recordings of cockpit instrumentation displays from United States Navy fighter jets based aboard aircraft carriers USS Nimitz and USS Theodore Roosevelt in 2004, 2014 and 2015, with additional footage taken by other Navy personnel in 2019. The four videos, widely characterized as officially documenting UFOs, have received extensive coverage in the media since 2017. The Pentagon later addressed and officially released the first three videos of unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP) in 2020, and confirmed the provenance of the leaked 2019 videos in two statements made in 2020.

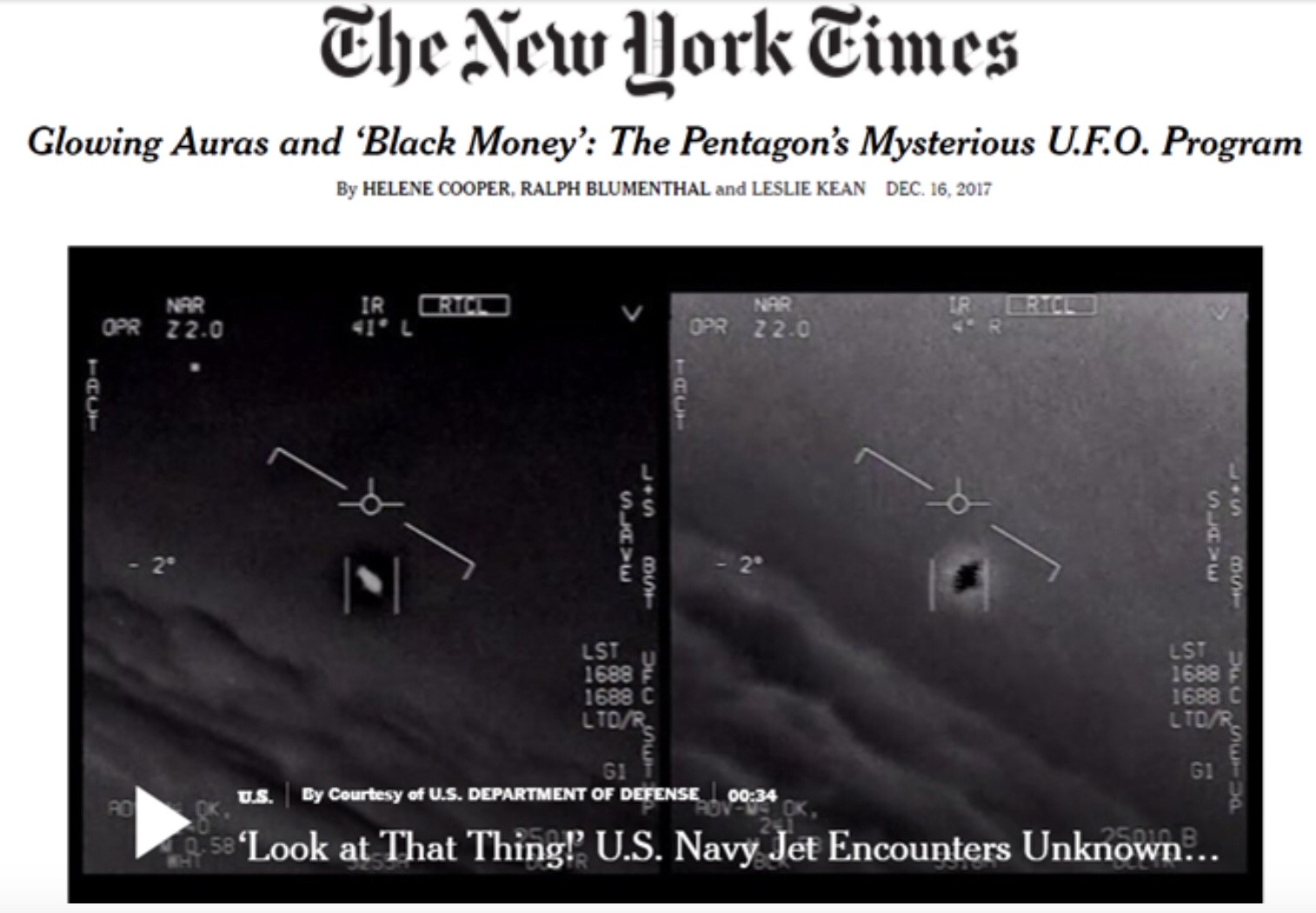

Below, are the original three videos that were leaked and later confirmed by the Pentagon.

The Events Leading up to the Pentagon UFO Video Disclosure

National Press Club - 2001

On May 9, 2001, Steven M. Greer took the lectern at the National Press Club, in Washington, D.C., in pursuit of the truth about unidentified flying objects. Greer, an emergency-room physician in Virginia and an outspoken ufologist, believed that the government had long withheld from the American people its familiarity with alien visitations. He had founded the Disclosure Project in 1993 in an attempt to penetrate the sanctums of conspiracy. Greer’s reckoning that day featured some twenty speakers. He provided, in support of his claims, a four-hundred-and-ninety-two-page dossier called the “Disclosure Project Briefing Document.” For public officials too busy to absorb such a vast tract of suppressed knowledge, Greer had prepared a ninety-five-page “Executive Summary of the Disclosure Project Briefing Document.” After some throat-clearing, the “Executive Summary” began with “A Brief Summary,” which included a series of bullet points outlining what amounted to the greatest secret in human history.

Over several decades, according to Greer, untold numbers of alien craft had been observed in our planet’s airspace; they were able to reach extreme velocities with no visible means of lift or propulsion, and to perform stunning maneuvers at g-forces that would turn a human pilot to soup. Some of these extraterrestrial spaceships had been

downed, retrieved and studied since at least the 1940s and possibly as early as the 1930s.”

Efforts to reverse engineer such extraordinary machines had led to “significant technological breakthroughs in energy generation.” These operations had mostly been classified as “cosmic top secret,” a tier of clearance “thirty-eight levels” above that typically granted to the Commander-in-Chief. Why, Greer asked, had such transformative technologies been hidden for so long? This was obvious. The “social, economic and geo-political order of the world” was at stake.

Greer’s “Executive Summary” was woolly, but discerning readers could find within it answers to many of the most frequently asked questions about U.F.O.s—assuming, as Greer did, that U.F.O.s are helmed by extraterrestrials. Why are they so elusive? Because the aliens are monitoring us. Why? Because they are discomfited by our aspiration to “weaponize space.” Have we shot at them? Yes. Should we shoot at them? No. Really? Yes. Why not? They’re friendly. How do we know?

Obviously, any civilization capable of routine interstellar travel could terminate our civilization in a nanosecond, if that was their intent. That we are still breathing the free air of Earth is abundant testimony to the non-hostile nature of these ET civilizations.”

At the press conference, Greer appeared in thin-framed glasses, a baggy, funereal suit, and a red tie askew in a starched collar. “I know many in the media would like to talk about ‘little green men,’ ” he said. “But, in reality, the subject is laughed at because it is so serious. I have had grown men weep, who are in the Pentagon, who are members of Congress, and who have said to me, ‘What are we going to do?’ Here is what we will do. We will see that this matter is properly disclosed.”

Among the other speakers was Clifford Stone, a retired Army sergeant, who purported to have visited crash sites and seen aliens, both dead and alive. Stone said that he had catalogued fifty-seven species, many of them humanoid. “You have individuals that look very much like you and myself, that could walk among us and you wouldn’t even notice the difference,” he said.

Leslie Kean, an independent investigative journalist and a novice U.F.O. researcher who had worked with Greer, watched the proceedings with unease. She had recently published an article in the Boston Globe about a new omnibus of compelling evidence concerning U.F.O.s, and she couldn’t understand why a speaker would make an unsupported assertion about alien cadavers when he could be talking about hard data. To Kean, the corpus of genuinely baffling reports deserved scientific scrutiny, regardless of how you felt about aliens. “There were some good people at that conference, but some of them were making outrageous, grandiose claims,” Kean said. “I knew then that I had to walk away.” Greer had hoped that members of the media would cover the event, and they did, with frolicsome derision. He also hoped that Congress would hold hearings. By all accounts, it did not.

After the Press Conference

In the years after the press conference, the expected announcement was apparently postponed by the events of September 11th, the War on Terror, and the financial crisis. In 2009, Greer issued a “Special Presidential Briefing for President Barack Obama,” in which he claimed that the inaction of Obama’s predecessors had “led to an unacknowledged crisis that will be the greatest of your Presidency.” Obama’s response remains unknown, but in 2011 ufologists filed two petitions with the White House, to which the Office of Science and Technology Policy responded that it could find no evidence to suggest that any “extraterrestrial presence has contacted or engaged any member of the human race.”

A Change in Perception

The government may not have been in regular touch with exotic civilizations, but it had been keeping something from its citizens. By 2017, Kean was the author of a best-selling U.F.O. book and was known for what she has termed, borrowing from the political scientist Alexander Wendt, a “militantly agnostic” approach to the phenomenon. On December 16th of that year, in a front-page story in the Times, Kean, together with two Times journalists, revealed that the Pentagon had been running a surreptitious U.F.O. program for ten years. The article included two videos, recorded by the Navy, of what were being described in official channels as “unidentified aerial phenomena,” or U.A.P. In blogs and on podcasts, ufologists began referring to “December, 2017” as shorthand for the moment the taboo began to lift. Joe Rogan, the popular podcast host, has often mentioned the article, praising Kean’s work as having precipitated a cultural shift. “It’s a dangerous subject for someone, because you’re open to ridicule,” he said, in an episode this spring. But now “you could say, ‘Listen, this is not something to be mocked anymore—there’s something to this.’ ”

Since then, high-level officials have publicly conceded their bewilderment about U.A.P. without shame or apology. Last July, Senator Marco Rubio, the former acting chairman of the Select Committee on Intelligence, spoke on CBS News about mysterious flying objects in restricted airspace. “We don’t know what it is,” he said, “and it isn’t ours.” In December, in a video interview with the economist Tyler Cowen, the former C.I.A. director John Brennan admitted, somewhat tortuously, that he didn’t quite know what to think:

Some of the phenomena we’re going to be seeing continues to be unexplained and might, in fact, be some type of phenomenon that is the result of something that we don’t yet understand and that could involve some type of activity that some might say constitutes a different form of life.”

Last summer, David Norquist, the Deputy Secretary of Defense, announced the formal existence of the Unidentified Aerial Phenomena Task Force. The 2021 Intelligence Authorization Act, signed this past December, stipulated that the government had a hundred and eighty days to gather and analyze data from disparate agencies. Its report is expected in June. In a recent interview with Fox News, John Ratcliffe, the former director of National Intelligence, emphasized that the issue was no longer to be taken lightly. “When we talk about sightings,” he said, “we are talking about objects that have been seen by Navy or Air Force pilots, or have been picked up by satellite imagery, that frankly engage in actions that are difficult to explain, movements that are hard to replicate, that we don’t have the technology for, or are travelling at speeds that exceed the sound barrier without a sonic boom.”

The COMETACenter Reportfor American Progress

In 1999, a journalist friend in Paris sent Leslie Kean a ninety-page report by a dozen retired French generals, scientists, and space experts, titled “Les OVNI et la Défense: À Quoi Doit-On Se Préparer?”—“U.F.O.s and Defense: For What Must We Prepare Ourselves?” The authors, a group known as COMETA, had analyzed numerous U.F.O. reports, along with the associated radar and photographic evidence. Objects observed at close range by military and commercial pilots seemed to defy the laws of physics; the authors noted their “easily supersonic speed with no sonic boom” and “electromagnetic effects that interfere with the operation of nearby radio or electrical apparatus.” The vast majority of the sightings could be traced to meteorological or earthly origins, or could not be studied, owing to paltry evidence, but a small percentage of them appeared to involve, as the report put it, “completely unknown flying machines with exceptional performances that are guided by a natural or artificial intelligence.” COMETA had resolved, through the process of elimination, that “the extraterrestrial hypothesis” was the most logical explanation.

An editor of the Boston Globe’s Focus section, who had admired Kean’s writing on Burma, tentatively agreed to work with her on a story about U.F.O.s. Kean chose not to discuss it with her KPFA colleagues, apprehensive that they would consider the topic, at best, frivolous. She was certain, though, that anyone given access to the French report’s data and conclusions would understand why she had dropped everything else. She refused to include any ironizing asides in the article, which was published on May 21, 2000, as a straightforward summary of the COMETA investigations. “But then, of course, nothing happened,” she said. “And that was the beginning of my education in the power of the stigma.”

In June of 2011, John Podesta invited Leslie Kean to make a confidential presentation at a think tank he founded, the Center for American Progress. Standing alongside a physicist from Johns Hopkins University and foreign military figures, Kean advised the audience—officials from NASA, the Pentagon, and the Department of Transportation, along with congressional staff and retired intelligence officials—that the challenge was “to undo fifty years of reinforcement of U.A.P. as folklore and pseudoscience.”

Podesta told me,Kean, “It wasn’t a bunch of people coming in looking like they were going to a ‘Star Wars’-memorabilia convention—it was serious people from the national-security arena who wanted answers to these unexplained phenomena.” Soon after the event, he said, a Democratic senator invited him for a meeting. “I thought it was going to be on food stamps and tax cuts or whatever, and the door closed and they said, ‘I don’t want anybody to know this, but I’m really interested in U.F.O.s, and I know you are, too. So what do you know?’ ”

The White House

In August, 2014, Kean visited the West Wing to meet again with Podesta, who was by then an adviser to President Obama. She had scaled down her request, proposing that a single individual in the Office of Science and Technology Policy be assigned to handle the issue. Nothing came of it. She was, however, a well-known figure on the international U.F.O. circuit and had a cordial relationship with the Chilean government’s Comité de Estudios de Fenómenos Aéreos Anómalos (CEFAA). She had begun breaking stories from its case files with an atypical recklessness. Kean’s work from this period, mostly published on the Huffington Post, shows signs of agitation and evangelism. In March of 2012, she wrote an article called “UFO Caught on Tape Over Santiago Air Base,” which referred to a video provided by CEFAA. Kean described the video as showing “a dome-shaped, flat-bottomed object with no visible means of propulsion . . . flying at velocities too high to be man-made.” She asked, “Is this the case UFO skeptics have been dreading?”

For the most part, people who do not feel that U.F.O.s represent a meaningful category of study regard the opposing view as a harmless curiosity. The world is full of weird, unaccountable convictions: some people believe that leaving your neck exposed in winter makes you ill, and others believe in U.F.O.s. But a small fraction of nonbelievers, known as “debunkers,” mirror ardent belief with equally ardent doubt. When Kean wrote about the CEFAA video, debunkers leaped at the chance to point out that the object in the case they had been dreading was in all probability a housefly or a beetle buzzing around the camera lens. Robert Sheaffer, the proprietor of a blog called Bad UFOs, wrote in his column in the Skeptical Inquirer, “Indeed, the very fact that a video of a fly doing loops is being cited by some of the world’s top UFOlogists as among the best UFO images of all time reveals how utterly lightweight even the best UFO photos and videos are.” Kean consulted with four entomologists, who mostly declined to issue a categorical judgment on the matter, and urged patience with CEFAA’s ongoing investigation.

“An informed skeptic is a very different thing from a debunker on a mission,” she wrote to me. “There are many out there who are on a mission to debunk UFOs at all costs. They’re not rational and they’re not informed.” Kean thought that they were blinded by zealotry. The skeptic Michael Shermer, for example, in a review of Kean’s book, had idly adduced that a wave of silent black triangles seen over Belgium in 1989 and 1990 were probably experimental, classified stealth bombers—despite official attestations to the fact that any government would be crazy to trot out its latest devices over heavily populated areas of Western Europe.

A tendency to discount or overlook inconvenient facts is a thing debunkers and believers have in common. One dogged British researcher has convincingly shown that the Rendlesham case, or Britain’s Roswell, probably consisted of a concatenation of a meteor, a lighthouse perceived through woods and fog, and the uncanny sounds made by a muntjac deer. Eyewitness reports are subject to considerable embroidery over time, and strings of improbable coincidences can easily be rendered into an occult pattern by a human mind prone to misapprehension and eager for meaning. The researcher had exhaustively demystified the case, and I was perturbed to learn that Kean seemed unfazed by his verdict. When I asked her about it, she did little more than shrug, as though to suggest that such fluky accounts violated Occam’s razor. Even if Rendlesham was “complex,” she said, it was still “one of the top ten U.F.O. encounters of all time.” And, besides, there were always other cases. Hynek, in “The UFO Experience,” had contended that U.F.O. sightings represented a phenomenon that had to be taken in aggregate—hundreds upon hundreds of incredible stories told by credible people.

Many U.F.O. debunkers are overtly hostile, but Mick West has a mild, disarming manner, one that only occasionally recalls the performative deference with which an orderly might cajole a patient back into his straitjacket. He grew up in a small mill town in northern England. His family did not have a television or a phone, and he learned to read with his father’s collection of Marvel comics. He was very good at math, and, after buying an early home computer with his earnings from a newspaper route, he became obsessed with primitive video games. As an adolescent, in the early nineteen-eighties, he loved science fiction, and was bewitched by a magazine called The Unexplained: Mysteries of Mind, Space and Time. The periodical was full of “true” stories about U.F.O.s and the paranormal—ghosts and the menacing creatures of cryptozoology. He used to lie in bed at night, as he wrote in his book, “Escaping the Rabbit Hole,” “literally trembling with the thought that some alien could enter my room and spirit me away to perform experiments on me.” Of particular cause for terror was the “Kelly-Hopkinsville encounter,” a 1955 case in which a Kentucky farmhouse was said to have come under attack by little green men.

As West became scientifically literate, he came to trust that the Kelly-Hopkinsville “aliens” were probably owls. Rather than cure his interest in the paranormal, however, this understanding refined it, and he began to take pleasure in the patient dismantling of unsound logic. This practice had, for West, therapeutic value, and as an adult his childhood anxieties are manifested only in a vestigial discomfort with the dark. In the nineties, West moved to California, where he co-founded a video-game studio; he is best known as one of the programmers behind the hugely popular Tony Hawk franchise. In 1999, the company he worked for was acquired by Activision, and, before the age of forty, he more or less retired. He found himself involved in Wikipedia edit wars concerning such contentious topics as homeopathy, scientific foreknowledge in sacred texts, and vegetarian lions. He eventually established his own Web site to combat the widespread misinformation surrounding Morgellons disease, an affliction with no established medical basis, which is characterized by the worry that strange fibres are emerging from one’s skin. Then he took on the chemtrails theory, and engaged with 9/11 truthers. As he put it in his book, “A small part of the reason why I debunk now (and still occasionally address ghost stories) is anger at the fear this nonsense instilled in me as a young child.”

West is a thoughtful, intelligent man. His e-mails feature numbered and lettered lists and light math. Everything he told me was perfectly persuasive, but even an hour on the phone with him left me feeling vaguely demoralized. Morgellons sufferers and chemtrail hysterics, he supposed, would be grateful to be relieved of their baseless fears, just as he had been disburdened of the psychic hazard posed by farmhouse aliens—and he didn’t see why U.F.O. advocates should be any different. He seemed unable to envisage that someone might find solace in the decentering prospect that we are not alone in a universe we ultimately know very little about.

In 2013, West founded Metabunk, an online forum where like-minded contributors examine anomalous phenomena. On January 6, 2017, another skeptic brought to his attention a Huffington Post piece by Kean. In the article, “Groundbreaking UFO Video Just Released by Chilean Navy,” Kean wrote in detail about an “exceptional nine-minute” film, shot on infrared cameras from a helicopter, that cefaa had been studying for two years. West watched the clip with an immediate sense of recognition. He posted the link to Skydentify, a Metabunk subforum, positing his theory that the video’s odd formations were “aerodynamic contrails,” which he was used to seeing as planes flew over his home in Sacramento. By January 11th, the community had ascertained that the purported U.F.O. was IB6830, a regularly scheduled passenger flight from Santiago to Madrid.

U.F.O. inquiries can proceed only through the process of elimination, a style of argument that is highly vulnerable to erroneous assumptions. In this case, as the Metabunk participants extrapolated, the helicopter pilots had inaccurately gauged the distance and altitude of the U.F.O., and viable possibilities—such as its being a commercial airliner in a takeoff climb—had been prematurely ruled out. West was not surprised. Although Kean regards pilots as “the world’s best-trained observers of everything that flies,” even Hynek determined, in 1977, that pilots are particularly prone to error. (He asserted, however, that “they do slightly better in groups.”) As West has written, “You can’t be an expert in the unknown.”

During one of my phone calls with Kean—greatly pleasurable distractions that tended to absorb entire afternoons—I mentioned to her that I had been in touch with Mick West. It was the only time I had known her to grow peevish. “If Mick were really interested in this stuff, he wouldn’t debunk every single video,” she said, almost pityingly. “He would admit that at least some of them are genuinely weird.”

Robert Bigelow

Robert Bigelow was three years old in the spring of 1947, when his grandparents were almost run off the road by a glowing object in the mountains northwest of Las Vegas. The Nevada desert of the early atomic age was one of the few places a child could see nuclear tests or rocket launches from his back yard, and Bigelow’s dreams of space exploration commingled with his curiosity about U.F.O.s. In the late nineteen-sixties, when he was in his early twenties, he began to invest in real estate—first in Las Vegas, then across the Southwest—and eventually he made a fortune with Budget Suites of America, a chain of extended-stay motels. Later, he founded a private company, Bigelow Aerospace, to build inflatable astronaut habitats. In 1995, he established the National Institute for Discovery Science, which described itself as “a privately funded science institute engaged in research of aerial phenomena, animal mutilations, and other related anomalous phenomena.” Among the consultants he hired was Hal Puthoff, whose work in paranormal studies dated back decades, to Project Stargate, a C.I.A. program to investigate how “remote viewing,” a form of long-distance E.S.P., might be useful in Cold War espionage. The next year, Bigelow purchased Skinwalker Ranch, a four-hundred-and-eighty-acre parcel a few hours southeast of Salt Lake City, named for a shape-shifting Navajo witch. Its previous owners had described being driven away by coruscating spheres, exsanguinated cattle, and wolflike creatures impervious to gunshots. In 2004, in the wake of a purported decrease in domestic paranormal activity, Bigelow shut down his institute, but he kept the ranch.

In 2007, Bigelow received a letter from a senior official at the Defense Intelligence Agency who was curious about Skinwalker. Bigelow connected him to an old friend from the Nevada desert, Senator Harry Reid, who was then the Senate Majority Leader, and the two men met to discuss their common interest in U.F.O.s. The D.I.A. official later visited Skinwalker, where, from a double-wide observation trailer on site, he is said to have had a spectral encounter; as one Bigelow affiliate described it, he saw a “topological figure” that “appeared in mid-air” and “went from pretzel-shaped to Möbius-strip-shaped.”

In 2008, Luis Elizondo, a longtime counterintelligence officer working in the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security, was visited by two people who asked him what he thought about U.F.O.s. He replied that he didn’t think about them, which was apparently the correct answer, and he was asked to join.

Bigelow believes, as one source put it to me, that “there are aliens walking around at the supermarket.” According to an article by MJ Banias, on the Web site the Debrief, Bigelow hired investigators to look into reports at Skinwalker of doglike creatures who smelled of sulfur and goblins with long, pendulous arms, as well as U.F.O. activity near Mt. Shasta. The program appears to have produced little more than a series of thirty-eight papers, all unclassified except one, about the kind of technology a U.F.O. might exploit—including work on the theoretical viability of warp drives and “spacetime metric engineering.” Bigelow’s researchers, convinced that crash debris was being hidden in some remote hangar, wanted access to the government’s classified data on U.F.O.s. In June, 2009, Senator Reid filed a request that the program be awarded “restricted special access program,” or SAP, status. The following month, BAASS issued a four-hundred-and-ninety-four-page “Ten Month Report.” The portions of the report that were leaked to Tim McMillan, along with additional sections that I was able to review, were almost exclusively about U.F.O.s, and the information provided was not limited to mere sightings; it included a photo of a supposed tracking device that supposed aliens had supposedly implanted in a supposed abductee. As one former government official told me, “The report arrived here and I read the whole thing and immediately concluded that releasing it would be a disaster.” In November, 2009, the Defense Department peremptorily denied the request for SAP status. (A representative of BAASS declined to comment for this article.)

Reid reached out to Senator Ted Stevens, of Alaska, who believed he’d seen a U.F.O. as a pilot in the Second World War, and Senator Daniel Inouye, of Hawaii. In the 2008 Supplemental Appropriations Bill, twenty-two million dollars of so-called black money was set aside for a new program. The Pentagon was not enthusiastic. As one former intelligence official put it, “There were some government officials who said, ‘We shouldn’t be doing this, this is really ridiculous, this is a waste of money.’ ” He went on, “And then Reid would call them out of a meeting and say, ‘I want you to be doing this. This was appropriated.’ It was sort of like a joke that bordered on an annoyance and people worried that if this all came out, that the government was spending money on this, this will be a bad story.” The Advanced Aerospace Weapon System Applications Program was announced in a public solicitation for bids to examine the future of warfare. U.F.O.s were not mentioned, but according to Reid the subtext was clear. Bigelow Aerospace Advanced Space Studies, or BAASS, a Bigelow Aerospace subsidiary, was the only bidder. When Bigelow won the government contract, he contacted the same cohort of paranormal investigators he’d worked with at his institute. Other participants were recruited from within the Pentagon’s ranks. In 2008, Luis Elizondo, a longtime counterintelligence officer working in the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security, was visited by two people who asked him what he thought about U.F.O.s. He replied that he didn’t think about them, which was apparently the correct answer, and he was asked to join.

Soon afterward, Elizondo, the counterintelligence officer, was asked to take over the program. Beginning in 2010, he turned an outsourced study of Utah cryptids into the Advanced Aerospace Threat Identification Program, or AATIP, an in-house effort that focussed on the national-security implications of military U.A.P. encounters. According to Elizondo, the program studied a number of incidents in depth, including what later became known as the “Nimitz encounter.”

The Nimitz Encounter

The Nimitz Carrier Strike Group was conducting training operations in restricted waters off the coast of San Diego and Baja California in November of 2004, when the advanced SPY-1 radar on one of the ships, the U.S.S. Princeton, began to register some strange presences. They were logged as high as eighty thousand feet, and as low as the ocean’s surface. After about a week of radar observations, Commander David Fravor, a graduate of the élite Topgun fighter-pilot school and the commanding officer of the Black Aces squadron, was sent on an intercept mission. As he approached the location, he looked down and saw a roiling shoal in the water and, hovering above it, a white oval object that resembled a large Tic Tac. He estimated it to be about forty feet long, with no wings or other obvious flight surfaces and no visible means of propulsion. It appeared to bounce around like a Ping-Pong ball. Two other pilots, one seated behind him and one in a nearby plane, gave similar accounts. Fravor descended to chase the object, which reacted to his maneuvers before departing abruptly at high speed. Upon Fravor’s return to the Nimitz, another pilot, Chad Underwood, was dispatched to follow up with more advanced sensory equipment. His aircraft’s targeting pod recorded a video of the object. The clip, known as “FLIR1”—for “forward-looking infrared,” the technology used to capture the incident—features one minute and sixteen seconds of a blurry ashen dot against a gunmetal background; in the final few seconds, the dot appears to outwit the FLIR track and make a rapid getaway.

Elizondo’s exposure to cases like the Nimitz encounter convinced him that U.A.P.s were real, but the government’s willingness to invest resources in the issue remained uncertain. Elizondo tried repeatedly to brief General James Mattis, the Secretary of Defense, about AATIP’s research, and was blocked by underlings. (General Mattis’s personal assistant at the time does not recall being approached by Elizondo.)

On October 4, 2017, at the behest of Christopher K. Mellon, a former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Intelligence, Leslie Kean was called to a confidential meeting in the bar of an upscale hotel near the Pentagon. She was greeted by Hal Puthoff, the longtime paranormal investigator, and Jim Semivan, a retired C.I.A. officer, who introduced her to a sturdy, thick-necked, tattooed man with a clipped goatee named Luis Elizondo. The previous day had been his last day of work at the Pentagon. Over the next three hours, Kean was taken through documents that proved the existence of what was, as far as anyone knew, the first government inquiry into U.F.O.s since the close of Project Blue Book, in 1970. The program that Kean had spent years lobbying for had existed the whole time.

After Elizondo resigned, he and other key AATIP participants—including Mellon, Puthoff, and Semivan—almost immediately joined To the Stars Academy of Arts & Science, an operation dedicated to U.F.O.-related education, entertainment, and research, and organized by Tom DeLonge, a former front man of the pop-punk outfit Blink-182. Later that month, DeLonge invited Elizondo onstage at a launch event. Elizondo announced that they were “planning to provide never-before-released footage from real U.S. government systems—not blurry amateur photos but real data and real videos.”

Kean was told that she could have the videos, along with chain-of-custody documentation, if she could place a story in the Times. Kean soon developed doubts about DeLonge, after he appeared on Joe Rogan’s podcast to discuss his belief that what crashed at Roswell was a reverse-engineered U.F.O. built in Argentina by fugitive Nazi scientists, but she had full confidence in Elizondo. “He had incredible gravitas,” Kean told me. She called Ralph Blumenthal, an old friend and a former Times staffer at work on a biography of the Harvard psychiatrist and alien-abduction researcher John Mack; Blumenthal e-mailed Dean Baquet, the paper’s executive editor, to say that they wanted to pitch “a sensational and highly confidential time-sensitive story” in which a “senior U.S. intelligence official who abruptly quit last month” had decided to expose “a deeply secret program, long mythologized but now confirmed.” After a meeting with representatives from the Washington, D.C., bureau, the Times agreed. The paper assigned a veteran Pentagon correspondent, Helene Cooper, to work with Kean and Blumenthal.

The New York Times Reveal

On Saturday, December 16, 2017, their story—“Glowing Auras and ‘Black Money’: The Pentagon’s Mysterious U.F.O. Program”—appeared online; it was printed on the front page the next day. Accompanying the piece were two videos, including “FLIR1.” Senator Reid was quoted as saying, “I’m not embarrassed or ashamed or sorry I got this going.” The Pentagon confirmed that the program had existed, but said that it had been closed down in 2012, in favor of other funding priorities. Elizondo claimed that the program had continued in the absence of dedicated funding. The article dwelled not on the reality of the U.F.O. phenomenon—the only actual case discussed at any length was the Nimitz encounter—but on the existence of the covert initiative. The Times article drew millions of readers. Kean noticed a change almost immediately. When people asked her at dinner parties what she did for a living, they no longer giggled at her response but fell rapt. Kean gave all the credit to Elizondo and Mellon for coming forward, but she told me, “I never would have ever imagined I could have ended up writing for the Times. It’s the pinnacle of everything I’ve ever wanted to do—just this miracle that it happened on this great road, great journey.”

It was hard to tell, however, what exactly AATIP had accomplished. Elizondo went on to host the History Channel docuseries “Unidentified,” in which he solemnly invokes his security oath like a catchphrase. He insisted to me that AATIP had made important strides in understanding the “five observables” of U.A.P. behavior—including “gravity-defying capabilities,” “low observability,” and “transmedium travel.” When I pressed for details, he reminded me of his security oath.

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a Pentagon project that had begun as a contractor’s investigation into goblins and werewolves, and had been reincarnated under the aegis of a musician best known for an album called “Enema of the State,” AATIP was subject to intense scrutiny. Kean is unwavering in her belief that she and an insider exposed something formidable, but a former Pentagon official recently suggested that the story was more complicated: the program she disclosed was of little consequence compared with the one she set in motion. Widespread fascination with the idea that the government cared about U.F.O.s had inspired the government at last to care about U.F.O.s.

Within a month of the Times article’s publication, the Pentagon’s U.A.P. portfolio was reassigned to a civilian intelligence official with a rank equivalent to that of a two-star general. This successor—who did not want to be named, lest U.F.O. nuts swarm his doorstep—had read Kean’s book. He channelled the cascade of media interest to argue that, without a process to handle uncategorizable observations, rigid bureaucracies would overlook anything that didn’t follow a standard pattern. At the height of the Cold War, the government had worried that the noise of lurid phantasmagoria might drown out signals relevant to national security, or even provide cover for adversarial incursions; now, it seemed, the concern was that valuable intelligence wasn’t being reported. (The Nimitz encounter didn’t become subject to official investigation until years after the incident, when an errant file landed on the desk of someone who decided that it merited pursuit.) “What we needed,” the former Pentagon official said, “was something like the post-9/11 fusion centers, where a D.O.D. guy can talk to an F.B.I. guy and an N.R.O. guy—everything we learned from the 9/11 Commission.”

In the summer of 2018, Elizondo’s successor brandished Kean’s article to make this case to members of Congress. According to the former Pentagon official, a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee inserted language into the classified annex of the 2019 National Defense Authorization Act, passed in August of 2018, that obligated the Pentagon to continue the investigations. “The U.A.P. issue is being taken very seriously now even compared to where it was two or three years ago,” the former Pentagon official said.

Ice cream truck with 'I Scream You Scream We All Scream Constantly' written on its side.

The activity intensified. In April of 2019, the Navy revised its official guidelines for pilots, encouraging them to report U.A.P.s without fear of scorn or censure. In June, Senator Mark Warner, of Virginia, admitted that he had been briefed on the U.A.P. matter. In September, a spokesperson for the Navy announced that the “FLIR1” video, along with two videos associated with sightings off the East Coast in 2015, showed “incursions into our military training ranges by unidentified aerial phenomena.” The “unidentified” label had been given an institutional imprimatur.

The debunkers were unimpressed by the designation, and their work continued apace. Mick West devoted multiple YouTube videos to his contention that “FLIR1” shows, in all likelihood, a distant plane. He maintained that the remainder of the available evidence from the Nimitz encounter was even shakier: he suspects that the presences picked up by the U.S.S. Princeton were probably birds or clouds, registered by a brand-new and likely miscalibrated radar system—the U.S.S. Roosevelt, off the East Coast, had also received a technological upgrade before a similar raft of sightings in 2014 and 2015—and that the Tic Tac-shaped object Commander Fravor saw was something like a target balloon. He has no explanation for what the other pilots saw, but points out that perceptions are subject to illusion, and memory is malleable.

Were our finest pilots and radar operators so inept that they were unable to recognize an airplane in restricted airspace? Or was the government using the word “unidentified” to conceal some deeply classified program that a branch of the service was testing without bothering to notify the Nimitz pilots? The former Pentagon official assured me that West “doesn’t have the whole story. There’s data he will never see—there’s much more that I would include in a classified environment.” He went on, “If Mick West feeds the stigma that allows a potential adversary to fly all over your back yard, then, cool—just because it looks weird, I guess we’ll ignore it.”

The point of using the term “unidentified,” he said, was “to help remove the stigma.” He told me, “At some point, we needed to just admit that there are things in the sky we can’t identify.” Despite the fact that most adults carry around exceptionally good camera technology in their pockets, most U.F.O. photos and videos remain maddeningly indistinct, but the former Pentagon official implied that the government possesses stark visual documentation; Elizondo and Mellon have said the same thing. According to Tim McMillan, in the past two years, the Pentagon’s U.A.P. investigators have distributed two classified intelligence papers, on secure networks, that allegedly contain images and videos of bizarre spectacles, including a cube-shaped object and a large equilateral triangle emerging from the ocean. One report brooked the subject of “alien” or “non-human” technology, but also provided a litany of prosaic possibilities. The former Pentagon official cautioned, “ ‘Unidentified’ doesn’t mean little green men—it just means there’s something there.” He continued, “If it turns out that everything we’ve seen is weather balloons, or a quadcopter designed to look like something else, nobody is going to lose sleep over it.”

Elizondo never got to Mattis, but his successor managed to get briefings in front of Mark Esper, the Secretary of Defense, as well as the director of National Intelligence, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, the Senate Armed Services Committee, and several members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Government officials in Japan later divulged to the media that they had discussed the topic in a meeting with Esper in Guam. When I asked the former Pentagon official about other foreign governments, he hesitated, then said, “We would not have moved forward without briefing close allies. This was bigger than the U.S. government.”

In June of 2020, Senator Marco Rubio added text into the 2021 Intelligence Authorization Act requesting—though not requiring—that the director of National Intelligence, along with the Secretary of Defense, produce “a detailed analysis of unidentified aerial phenomena data and intelligence reporting.” This language, which allowed them a hundred and eighty days to produce the report, drew heavily from proposals by Mellon, and it was clear that this concerted effort, at least in theory, was a more productive and more cost-effective iteration of the original vision for AATIP. Mellon told me, “This creates an opening and an opportunity, and now the name of the game is to make sure we don’t miss that open window.”

Still, the former Pentagon official told me, “it wasn’t until August of 2020 that the effort was really real.” That month, the Deputy Secretary of Defense, David Norquist, publicly announced the existence of the Unidentified Aerial Phenomena Task Force, whose report is anticipated in June. The Intelligence Authorization Act finally passed in December. The former Pentagon official worries that an appetite for disclosure has been heedlessly stoked. “The public, I would hope, doesn’t expect to see the crown jewels,” he said.

West was nonchalant. “They’re just U.F.O. fans,” he said of Reid and Rubio. “They’ve been convinced there’s something to it and so are trying to push for disclosure.” The former Pentagon official conceded that there were “a lot of government people who are enthusiasts on the subject who watch the History Channel and eat this stuff up 24/7.” But, he said, the current mood was by no means set by “a small cadre of true believers.”

Virtually all astrobiologists suspect that we are not alone. Seth Shostak, the senior astronomer at the SETI Institute, has wagered that we will find incontrovertible proof of intelligent life by 2036. Astronomers have determined that there may be hundreds of millions of potentially habitable exoplanets in just our galaxy. Interstellar travel by living beings still seems like a wildly remote possibility, but physicists have known since the early nineteen-nineties that faster-than-light travel is possible in theory, and new research has brought this marginally closer to being achievable in practice. These advances—along with the further inference that ours is a mediocre or even inferior civilization, one that could well be millions or billions of years behind our distant neighbors—have lent a bare-bones plausibility to the idea that U.F.O.s have extraterrestrial origins.

Such a prospect, as Hynek wrote in the mid-nineteen-eighties, “overheats the human mental circuits and blows the fuses in a protective mechanism for the mind.” Its destabilizing influence was clear. I would begin interviews with sources who seemed lucid and prudent and who insisted, like Kean, that they were interested only in vetted data, and that they used the term “U.F.O.” in the strictly literal sense—whether the objects were spaceships or drones or clouds, we just didn’t know. An hour later, they would reveal to me that the aliens had been living in secret bases under the ocean for millions of years, had genetically altered primates to become our ancestors, and had taught accounting to the Sumerians.

Since 2017, Kean has covered the U.F.O. beat for the Times, sharing a byline with Ralph Blumenthal on a handful of stories. These have steered clear of such genre mainstays as crop circles and Nazca Lines, but their most recent article, published last July, veered into fringe territory. In it, they referred to “a series of unclassified slides,” of somewhat uncertain lineage but apparently shown at congressional briefings, that mentioned “off-world” vehicles and “crash retrievals.” Kean told me in an uncharacteristically hesitant but nonetheless matter-of-fact way that she had begun to come around to the idea that U.F.O. fragments had been hoarded somewhere. In 2019, Luis Elizondo had suggested to Tucker Carlson that such detritus existed. (He then quickly invoked his security oath.) Kean cited Jacques Vallée, perhaps the most famous living ufologist, and the basis for François Truffaut’s character in “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” who has been working with Garry Nolan, a Stanford immunologist, to analyze purported crash material for scientific publication. (Vallée declined to speak about it on the record, concerned that it might undermine the peer-review process, but told me, “We hope it will be the first U.F.O. case published in a refereed scientific journal.”)

In the story, Kean and Blumenthal wrote that Harry Reid “believed that crashes of vehicles from other worlds had occurred and that retrieved materials had been studied secretly for decades, often by aerospace companies under government contracts.” The day after its publication, the Times had to append a correction: Senator Reid did not believe that crash debris had been allocated to private military contractors for study; he believed that U.F.O.s may have crashed, and that, if so, we should be studying the fallout. When I asked Reid about the confusion, he told me that he admired Kean but that he had never seen proof of any remnants—something Kean had never actually claimed. He left no doubt in our conversation as to his personal assessment. “I was told for decades that Lockheed had some of these retrieved materials,” he said. “And I tried to get, as I recall, a classified approval by the Pentagon to have me go look at the stuff. They would not approve that. I don’t know what all the numbers were, what kind of classification it was, but they would not give that to me.” He told me that the Pentagon had not provided a reason. I asked if that was why he’d requested SAP status for AATIP. He said, “Yeah, that’s why I wanted them to take a look at it. But they wouldn’t give me the clearance.” (A representative of Lockheed Martin declined to comment for this article.)

The former Pentagon official told me that he found Kean’s evidence wanting. “There are terms in Leslie’s slides that we don’t use—stuff we would never say,” he said. “It doesn’t pass the smell test.” But, when I asked him whether he thought that there might be recovered debris somewhere, he paused for a surprisingly long time. He finally said, “I couldn’t say yes, like Lue”—Luis Elizondo—“did. I honestly don’t know.” He continued, “There are guys who spent their lives studying stuff like Roswell and died with no answers. Are we all going to die with no answers?”

Not everyone needs answers, or expects the government to provide them. In February, I spoke to Vincent Aiello, a podcaster and former fighter pilot, who served on the Nimitz at the time of the encounter. He told me that the widespread impression of Commander Fravor’s story back then, thirteen years before it became a news sensation, was that it sounded pretty far out, but that the gossip and laughter on the ship petered out after a day or two. “Most military aviators have a job to do and they do it well,” he said. “Why pursue life’s great mysteries when that’s what Geraldo Rivera is for?”

The mysteries have shown no signs of abatement. In early April, the eminent U.F.O. journalist George Knapp, along with the documentary filmmaker Jeremy Kenyon Lockyer Corbell, best known for his participation in an ill-begotten crusade to “storm” Nevada’s Area 51, released a video and a series of photos that had apparently been leaked from the U.A.P. Task Force’s classified intelligence reports. The video, taken with night-vision goggles, shows three airborne triangles, intermittently flashing with eerie incandescence as they rotate against a starry sky. Kean texted me, “Breaking huge story.” She was trying to get to the bottom of the video, but doubted that any of her sources would be willing to authenticate something so hot. The next day, the Department of Defense confirmed that the video was real and said that it had been taken by Navy personnel. Mick West argued, persuasively, that the pyramids were an airplane and two stars, distorted by a lens artifact. Kean, for her part, told me that she was “only just starting to look into the situation,” but volunteered that West was “being reasonable.” The Pentagon refused further comment.

The government may or may not care about the resolution of the U.F.O. enigma. But, in throwing up its hands and granting that there are things it simply cannot figure out, it has relaxed its grip on the taboo. For many, this has been a comfort. In March, I spoke with a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force who said that about a decade ago, during combat, he had an extended encounter with a U.F.O., one that registered on two of his plane’s sensors. For all the usual reasons, he had never officially reported the sighting, but every once in a while he’d bring a close friend into his confidence over a beer. He did not want to be named. “Why am I telling you this story?” he asked. “I guess I just want this data out there—hopefully this helps somebody else somehow.”

The object he’d encountered was about forty feet long, disobeyed the principles of aerodynamics as he understood them, and looked exactly like a giant Tic Tac. “When Commander Fravor’s story came out in the New York Times, all my buddies had a jaw-drop moment. Even my old boss called me up and said, ‘I read about the Nimitz, and I wanted to say I’m so sorry I called you an idiot.’ ”

UAP Report to Congress

On June 25, 2021 the office of the Director for National Intelligence produced a report for the U.S. Congress entitled "Preliminary Assessment: Unidentified Aerial Phenomena". In it, the newly formed Unidentified Aerial Phenomena Task Force (UAPTF) that conducted the study for the report, said

The limited amount of high-quality reporting on unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP)

hampers our ability to draw firm conclusions about the nature or intent of UAP."

and went further to say

Most of the UAP reported probably do represent physical objects given that a

majority of UAP were registered across multiple sensors, to include radar, infrared,

electro-optical, weapon seekers, and visual observation.

However, the report fell short of stating the objects were of extraterrestrial origin. Instead, grouping any unexplained objects simply as "other".

Sources

- "How the Pentagon Started Taking U.F.O.s Seriously". Gideon Lewis-Kraus. The New Yorker April 30, 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/05/10/how-the-pentagon-started-taking-ufos-seriously

- "Glowing Auras and ‘Black Money". Helen Cooper, Ralph Blumenthal, Leslie Kean. The New York Times. December 16, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com › 2017 › 12 › 16 › us › politics › pentagon-program-ufo-harry-reid.html

- OFFICE of the DIRECTOR of NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE. https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/Prelimary-Assessment-UAP-20210625.pdf